Films come, and films go, but very few have managed to carve a cult niche for themselves the way Pulp Fiction has. Over time, and millions of critics tearing down every aspect of the film, Pulp Fiction has sustained to become one of the most iconic films of all time, rightfully finding its place in lists of all-time greatest films ever made. Even beyond a hardcore film critic’s point of view, Pulp Fiction is one film that remains in the viewer’s mind, even after 21 years of its premiere. Here’s listing 8 reasons and moments from a film which has defined filmmaking and affected so many of us, over time!

1. Ezekiel 25:17…

This one had to top the list, with Samuel L. Jackson etching out a space for Jules Winnfield on the audience’s mind. The actual passage is not off the Bible, and was originally scripted for Tarantino’s From Dusk Till Dawn. Additionally, with this verse, Tarantino paid a quiet homage to the 1979 film Karate Chiba, where a nearly identical passage is narrated. Nevertheless, Jules’ recitation of this passage has constantly been rated as one of the top ten passages ever spoken in films, and till date, remains to be one of the prime identifiers of Pulp Fiction.

2. The use of direct violence

Pulp Fiction has been a trendsetter in more ways than one, and among them, features the use of direct violence. Be it the breakfast scene where Jules and Vincent shoot Bret from point-blank range, to Marvin getting shot right on the face “accidentally”, Pulp Fiction set the tone for direct scenes of violence in movies to follow. Take for instance Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels that premiered in 1998, four years after Pulp Fiction, and you already notice the impact of the on-film violence that Pulp Fiction showed. It also made us grew up, and showed us how violence looks like, on the face of it.

3. The (in)famous wallet

Such is the widespread presence of individual elements in Pulp Fiction, that a wallet introduced almost at the very end of the film is remembered now by almost everyone. Jules Winnfield’s wallet had the words ‘Bad Motherf****r’ written on it, thereby imparting an iconic status to a film that is already overloaded by moments and scenes standing out as highly independent elements within it.

4. The now-iconic dance scene

While many popular theories have taken the iconic Mia Wallace-Vincent Vega dance scene as tailor-made for John Travolta (Saturday Night Fever?), it was actually Tarantino’s subtle homage to a scene from Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande a Part (1964). In Tarantino’s own words, “(The) scene existed before John Travolta was cast. But once he was cast, it was like, “Great. We get to see John dance. All the better.”… My favorite musical sequences have always been in Godard, because they just come out of nowhere. It’s so infectious, so friendly. And the fact that it’s not a musical, but he’s stopping the movie to have a musical sequence, makes it all the more sweet.”

5. Resurgence of John Travolta and Bruce Willis

When Pulp Fiction came out in the year 1994, John Travolta was in a 14-year-long slump. His last profitable work was Urban Cowboy in 1980, and Saturday Night Fever was three years before that. Pulp Fiction attained the cult status across generations to come, and John Travolta’s career slump revived to give us the likes of Get Shorty (1995), Face/Off (1997) and Primary Colours (1998).

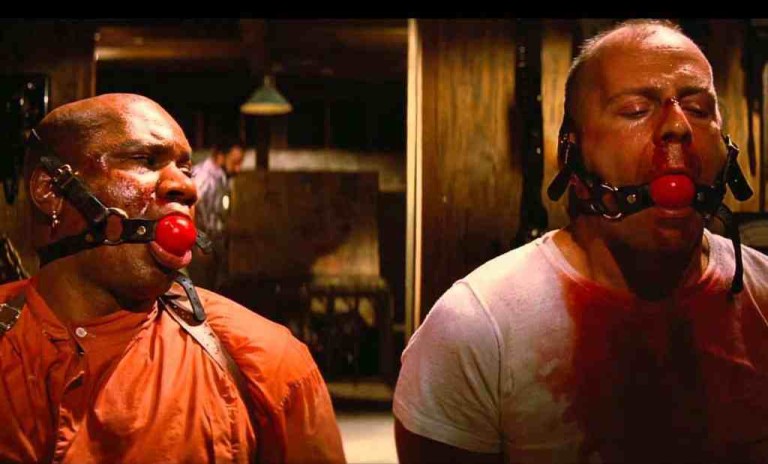

Bruce Willis, arguably, was doing better than Tarantino with Die Hard. But, what the post-Pulp Fiction world saw was a different side of Willis – the one that gave us the likes of The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000) and Sin City (2005).

6. The Briefcase

You will never know what the golden glow actually meant, and there have been many theories to it. While the most popular was that it contained Marsellus Wallace’s soul – which he had traded with the Devil for wealth and power, then had it stolen back from him – many have disowned such notions (the lock combination of ‘666’ makes it somewhat fitting, though). The band-aid on Wallace’s neck was not intentional, meaning that this was probably not what Tarantino aimed for. Other explanations simply state that it’s a MacGuffin, or Elvis’ golden suit, or even an oscar (you could almost hear Tarantino doubling up in laughter), but the briefcase has been one of the most noted elements in film over the last two decades, and will continue to be so.

7. The iconic soundtrack

Dick Dale’s Misirlou rendition is as recognisable as the intro riff of Smoke on the Water. The opening track has given way to one of the most recognisable and unconventional soundtracks in film – with parts of it containing sections of dialogue and interceptions in between tracks. The 41-minute soundtrack had other iconic tracks like Bustin’ Surfboards by The Tornadoes, Jungle Boogie by Kool & the Gang, and drew favourable reviews from critics and fans alike.

8. Studies, criticisms, teardowns

In 2013, a survey rated Quentin Tarantino as the most-studied film director in the United Kingdom, followed by Christopher Nolan. Pulp Fiction is the shining icon in Tarantino’s arsenal, and has always been a subject of study, scrutiny and criticism among film students, enthusiasts and critics alike. Be it the complete disregard to the linear convention of storytelling, to the bold, rebellious face of violence depicting itself the way it hits in reality, Pulp Fiction has been widely studied and examined, giving the film industry and example and trend of standing out amidst all the crowd and ruckus of overdone storylines.

To sum up, Pulp Fiction is a work of art that stood up and defied the existence of a different world within celluloid – it embraced the kaleidoscope of accidents, and the vulnerability of tough mercenaries to be disturbed at a casual mention of a foot massage, to give out far wider implications than just being a great film.

Two decades on, and Pulp Fiction has spawned an inspired style of filmmaking that refers to a film that itself has paid tribute to some of the choicest films of the ‘50s and ‘60s.